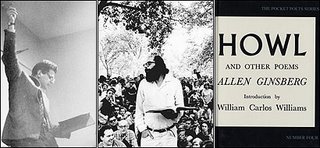

Allen Ginsberg (left) reading in San Francisco on Nov. 20, 1955, and (center) in New York City's Washington Square Park on Aug. 28, 1966. At right, the City Lights Pocket Poets edition of 'Howl and Other Poems.'

Allen Ginsberg (left) reading in San Francisco on Nov. 20, 1955, and (center) in New York City's Washington Square Park on Aug. 28, 1966. At right, the City Lights Pocket Poets edition of 'Howl and Other Poems.'By David Barber | April 30, 2006

The Boston Globe

POETRY MAKES NOTHING happen, Auden duly informs us, but when mythology takes over, anything goes. Or so it would seem, to judge by a new collection of essays, ''The Poem That Changed America: 'Howl' Fifty Years Later" (FSG), commissioned by Beat hagiographer Jason Shinder to mark the golden anniversary of Allen Ginsberg's epochal barbaric yawp.

Ever since ''Howl" first appeared in its instantly talismanic City Lights pocket edition in the fall of 1956, it's been hard to reckon where the poetry ends and the mythology begins. The Poem That Changed America? Never mind that there's no parsing such a blunderbuss hypothesis-the startling thing is that any poem at this late date can still have the kind of potent half-life in the collective imagination usually reserved for platinum pop hits.

When the legend becomes fact, runs the imperishable line in John Ford's ''The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance," print the legend. In the case of ''Howl," it was a seamless transition: The poem was already legendary before it saw the light of print.

In the standard telling, it all began with a thunderclap on what Jack Kerouac later called that ''mad night" of Oct. 7, 1955, in an erstwhile San Francisco auto-body shop converted to a Boho art gallery. That was the mad night Ginsberg took his turn on the orange-crate podium and declaimed his work in progress to the assembled ''angelheaded hipster" faithful, leaving the throng in an uproar and Beatnik paterfamilias Kenneth Rexroth in tears. That was the mad night that Ginsberg's full-throttle first line-"I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked"-burst into the American vernacular as the first and perhaps still unbested of countless generational war cries. That was the mad night that turned a spindly Jewish twentysomething from Jersey into a rock star avant la lettre, prompting ever-canny City Lights impresario Lawrence Ferlinghetti to fire off a telegram the next day that echoed Emerson's storied note to Whitman on the publication of ''Leaves of Grass" exactly a century earlier: ''I greet you at the beginning of a great career."

It's the stuff of fable, and it goes to show that there's nothing like a classic creation myth for industrial-strength staying power. That night has gone down in the annals as the official kickoff of the San Francisco Renaissance as a brand-name literary movement, but that's not the half of it. There was an earthquake that night, and it presaged the birth of the counterculture, the spawning of Sixties youth rebellion, and the annunciation of redemptive transgression as a radical social creed and a libertine fashion statement.

''Howl" was its epicenter, and the fault lines would be redrawn as battle lines practically overnight. By the time the revised text began to circulate far and wide as Beatnik samizdat, complete with a lionizing benediction by Ginsberg's old hometown mentor William Carlos Williams (''Hold back the edges of your gowns, Ladies, we are going through hell"), ''Howl" was already more of a landmark cultural artifact than a mere work of literature, the breakneck lines on the page barely able to keep up with the zeitgeist whirlwind they were reaping.

Pop culture chronology is of course the inverse of geological time-a year is an era and half a century is the rock of ages. It may appear more inevitable than ironic, then, that Ginsberg's brave new caterwaul was destined to be remastered as an Old School anthem.

The conclave Shinder has rounded up is a conspicuously mixed bunch (professors and pundits ranging from Marjorie Perloff to Andrei Codrescu jostle with assorted literati like Marge Piercy, Rick Moody, and former US poet laureates Billy Collins and Robert Pinsky) and the plan was clearly to size up the ''Howl" phenomenon from every conceivable angle ('''Howl' and the Language of Modernism," '''Howl' in Transylvania," ''The Poet as Jew"). Taken together, though, it all rather smacks of committee work, a laborious bureaucratic effort to affirm that ''Howl" is still everything it's cracked up to be, and then some. This predictably leads to a good deal of boilerplate prattle-"'Howl,' so perfectly titled, was coolness, madness, anger, and some of the secular beatitudes all wrapped into one poem," Collins chirps. Nevertheless, there's a suitably thoroughgoing remedial education to be had for those of tender years whose strongest recall of Allen Ginsberg may be as one of those dudes in the retro Gap khaki ads.

Despite some faint traces of disenchantment in the air, the festschift's prevailing tenor is pious, even starstruck, as the eclectic panel queues up to attest to ''Howl"'s totemic mystique and revolutionary vibe, albeit at times straining mightily to dissolve any contradiction between the poem's iconoclastic clamor and its canonic stature. That's mythic grandeur for you, but it's also a case of dutifully taking the poet at his own word. ''In publishing 'Howl,"' Ginsberg avowed in a brief retrospective piece the anthology reprints under the oddly poignant title ''I've Lived with and Enjoyed 'Howl'," ''I was curious to leave behind after my generation an emotional time bomb that would continue exploding in US consciousness in case our military-industrial-nationalist complex solidified into a repressive police bureaucracy."

. . .

In the face of such commemorative fanfare, it almost seems churlish to retort that the time bomb has come to more closely resemble a time capsule. That's not to say ''Howl" and its cult following haven't had a china-rattling cultural impact: There's no arguing with the archival evidence that the poem administered a genuine shock to the body politic and body poetic alike. But what if its unreconstructed acolytes have it exactly backwards, and the enduring allure of ''Howl" has less to do with its groundbreaking raw language, and its rip-roaring sales pitch for a new brand of antiestablishment enlightenment, than with what a defiantly old-fashioned poem it is? What if its ''powerful resonance today," as the anthology's flap copy trumpets, is an elegiac rather than a prophetic echo, a last gasp instead of a clarion call?

We are talking about a poem, after all, that's modeled on ancient prosodic blueprints, bardic and Biblical: the litany, the psalm, the dithyramb, the catalog. It's a poem whose original working title was ''Strophes," knowingly harking back to the incantatory template of Attic choral odes and Athenian tragedies. It's a poem inescapably cosponsored by those two magisterial 19th-century rhapsodists, Blake and Whitman-and not merely in its impassioned appropriation of their soundtracks (great rolling cadences, cascading refrains, margin-busting line measures) but also their mindscapes (ecstatic hyperbole, cosmic visions, declamatory speechifying). Its hyperventilating denunciation of ''Moloch" as the personification of the soul-corrupting social order (''Moloch whose mind is pure machinery! Moloch whose blood is running money!") is a trope straight out of Old Testament scripture; its feverish ''Footnote" (''Holy the groaning saxophone! Holy the bop apocalypse!") is nothing less than an amped-up liturgical chant. We are talking about a poem, in other words, that's animated by the most atavistic article of faith in the book-the power and glory of poetic utterance itself.

The party line on ''Howl" pays lip service to all this, but what's seldom owned up to is how dolefully retrograde it now feels to take Ginsberg's explosive poem-any poem-on those sacramental terms. It's safer to exalt ''Howl"'s vehemence at the expense of its earnestness; it's easier to buy into its subversive scatalogical explicitness than to put stock in its subversive absence of irony. A San Francisco magistrate's ruling in the 1957 City Lights obscenity trial that the poem has ''some redeeming social importance" assured that its uncensored publication would go down as a thumping victory for trash-talking free speech and fire-breathing political dissent, and yet in another sense it was a coup de grace: Enshrining ''Howl" as a social manifesto seems to have had the irreversible effect of embalming it as a period piece.

''The appeal in 'Howl' is to the secret or hermetical tradition of art 'justifying' or 'making up for' defeat in worldly life," Ginsberg later wrote, but the erudite ring of that remark is just one more chastening reminder of how the spirit in which his poem was conceived has been swallowed up by the theatrical spectacle of its public acclaim. The notoriety of Ginsberg's opus as an all-purpose, pocket-sized rite of passage-part do-it-yourself kit for demolishing taboos, part passport to polymorphous permissiveness-scarcely afforded ''Howl" the fighting chance to earn its keep as a poem. Indeed, it's hard to dispel the impression that the most dated thing about the poem is that it is a poem.

So are ''Howl"'s latter-day adherents succumbing to false nostalgia in proclaiming the poem as a national monument? Not at all: The nostalgia is genuine. It's surely wishful thinking to imagine that poetry was ever close to the center of American public life, but in the clear light of hindsight it sure looks like it was within closer hailing distance once upon a time than seems remotely plausible today. If Ginsberg's message has stood the test of time better than his medium, that may be the real secret as to why his dirge still touches such a raw nerve. Poems don't set our ears on fire like that anymore, and they know better than to even try.

David Barber is poetry editor of The Atlantic